If Preston North End were a pop band, they would be those boisterous lads from across the South Pennines, the Kaiser Chiefs.FN1 Their first album would have gone six-times platinum and spawned four hit singles, then they would have scored one more major hit before drifting into harmless obscurity, their members known for their celebrity status rather than the music they produce. They would continue to fill arenas (Deepdale had an average gate of nearly 11,000 in the 2014/2015 League One [3] season[1] ) but even their most die-hard fans would probably admit to longing for bygone days.

‘Thrills for all’ promised by the Kaiser Chiefs and the Preston Invincibles alike

Though I mock, it cannot be denied that the first Kaiser Chiefs album still stands up to scrutiny 11 years on – and more importantly for my metaphor, it’s status as one of the most influential records of the last decade or so is surely not up for debate. It’s title also chimes nicely with the Preston story because, in an audacious move that would have huge repercussions for football and British society in general, Employment is exactly what the Football League’s first superpower offered to its players.

Association football was supposed to be a strictly amateur affair, enjoyed by well-schooled gentlemen who, if they weren’t busy kicking each other on a muddy football field, would otherwise have had to occupy themselves running the country, businesses or the armed forces. The mistake the ruling classes made with football was that it was a simple game that required only a ball, a couple of other chaps and a small space to play. Cricket needs specialist equipment and it’s hard to have a game of rugby in the cobbled streets of an industrial town, so it was only inevitable that in the mid-1800s, football was the upper-class sport that gained a foothold in the working-class provinces.

Preston North End in particular found this out the hard way. They were founded by local businessmen (of the emerging middle-class) as a cricket club in 1863 (the same year the Football Association was created in London) and also tried their hand at rugby, athletics, lacrosse and even rounders, before realising football was the game that would bring crowds to the Deepdale ground they had acquired in 1875, a necessary step as the club was in dire financial straits for much of the decade.[2] Their first game under Association rules took place in 1878 and they dropped their other sporting interests three years later.

By this time, de facto professionalism was already emerging in the North West. In 1884, Blackburn Olympic became the first team featuring working-class players to win the FA Cup. Though paying wages was strictly forbidden by FA rules, many of the factory owners and brewers who funded northern clubs found suitably cushy roles within their primary businesses for the best local talent. The Olympic team even included two players ‘imported’ from Sheffield under this type of arrangement.[3]

It was Preston who would take this concept to the next level, under the guidance of one William ‘Billy’ Sudell. A privately educated manager at his father’s cotton warehouse, Sudell had become Preston’s chairman in 1874 (while in his mid-20s) and it was he who pointed to the success of Lancashire’s football clubs as the model North End should follow.FN2

Much to the chagrin of the gentlemen of the FA, in the 1880s Sudell began building his team around players tempted south from Scotland and given ‘jobs’ locally. These ringers were nicknamed ‘Scotch professors’, owing to the more methodical style of passing that had emerged with the Queen’s Park club in Glasgow in the late-1860s (as opposed to the rough-and-tumble hacking and charges that were a feature of the public school game).

This was regarded by the establishment as altogether sneaky behaviour and in January 1884, Preston were thrown out of the FA Cup for ‘remunerating’ a player. This incident sparked a bitter divide in the footballing community, a class war that would occasionally turn to violence between players and supporters subscribing to the rival philosophies.[4] However, the tide of professionalism was unstoppable, compared to ‘the flow of Niagara’ by the progressive Celtic board member John McLaughlin.[5] FN3 It took just over 18 months for the campaign, spearheaded by the visionary Sudell, to win official sanctioning for players to start receiving wages, allowing working-class men to commit to the game without fear that injury would keep them away from their real work.

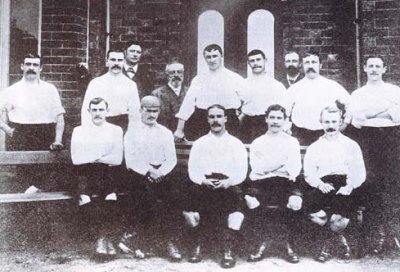

William Sudell (back row, third from left) and his ‘Invincibles’

The new rules said players must reside within six miles of a club’s ground for a minimum of two years before they could be paid, but Preston had already stolen a march on most clubs with their Scottish professors.[6] They were being called ‘The Invincibles’ even before the unbeaten inaugural Football League campaign of 1888/89, losing only a handful of the friendlies and Cup matches they played in the years prior to this. Unfortunately two of these were crucial FA Cup ties, the first a semi-final (1887) and then a final (1888), both against West Bromwich Albion.

This meant, for all Sudell had achieved and all that Preston’s exciting style of play was admired, the League title of 1888/89 was their first trophy. In 22 games they amassed 18 wins and a goal difference of +59 (their nearest rivals, Aston Villa, had one of just +18), enough to wrap up the championship by January, before the Cup competition even started.[7] Later that season they finally avenged themselves upon West Brom to reach another Cup Final and beat Wolverhampton Wanderers 3-0 at the Oval, having kept a clean sheet in every round.

But the success was short-lived and, as other teams followed Preston’s recruitment model, the Invincibles turned out to be vincible after all.FN4 They retained their League title in 1890, but were runners-up for the next three seasons and didn’t reach the FA Cup Final again until 1922.

North End won the Cup for the second and last time in 1938, beating Huddersfield Town (the club they had lost to in 1922) at Wembley thanks to a penalty in the dying minutes of extra time. This proved to be their ‘Ruby’ moment – their last taste of a number one hit.

Shortly after this, a young man by the name of Thomas Finney signed professional terms, prior to becoming one of the post-war era’s greatest players and finest characters. For all Billy Sudell had done to legitimise what the gentlemanly amateurs regarded as scourge of the footballing mercenary, 60 years on Finney came to represent the now increasingly rare ideal of a local boy’s loyalty to his hometown club. Though thoroughly working class, he was by all accounts the embodiment of the modern meaning of the word ‘gentleman’.

The two-time ‘Footballer of the Year’ almost single-handedly led his club to the 1954 FA Cup Final and runners-up spot in the League [1] in 1958, but after his retirement in 1960, Preston were relegated from the top flight, never to return. In 1964 they surprised everyone by reaching one more Cup Final and took the lead twice, before Bobby Moore’s West Ham side finally won the match 3-2.FN5

Some football clubs, like most bands, are destined to flourish early and never again. I don’t mean to dismiss either Preston or the Kaiser Chiefs’ potential to ever return to the big time, but just as most conversations about the latter will revolve around how good a début single ‘Oh My God’ was and Ricky Wilson’s cheeky charm on The Voice, so brief histories of Preston North End will tend to dwell on Billy Sudell’s Invincibles, with a brief afterthought about what a thoroughly nice chap Tom Finney was.

Footnotes

- FN1The Kaizer Chiefs, of course, are a football club, based in Johannesburg.

- FN2Sudell also found time to campaign for the Liberal Party and rise to the rank of Major in the local Volunteer Force.

- FN3McLaughlin’s full quote was, ‘You might as well attempt to stop the flow of the Niagara with a kitchen chair as to endeavour to stem the tide of professionalism.’

- FN4Yes, that is a word: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/vincible

- FN5In this match, Preston’s left-half Howard Kendall set a new record for the youngest player in a Cup Final, at 17 years and 345 days.