I suppose the first question to ask is why Cardiff City – and five others teamsFN1 – are included in a supposed history of ‘English’ football in the first place. It’s a difficult one to answer without insulting any Welsh readers, because it comes down to two things to the detriment of their fine country: the first is that the likes of Cardiff, Swansea and Wrexham were simply too good to play in Wales; the second is that Wales is a pretty hopeless place to football at all.

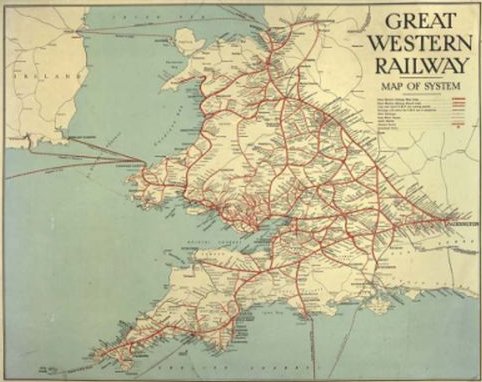

The Great Western Railway pre-Beeching

Let me clarify that. It’s a pretty hopeless place to play a football league. In the early part of the twentieth century – as, let’s face it, is still the case – getting around Wales was significantly harder than it was the rest of the United Kingdom. Establishing a national league in Wales would involve clubs from the north and south having to cross the mountainous regions between or circumvent them via the west coast. Even before Dr Beeching got carried away with his eraser in the 1960s, north-south train travel in Wales meant going via Aberystwyth – now it means going via Shrewsbury.[1]

The upshot of this was that Welsh clubs tended to look east when they wanted to find opposition. Cardiff’s early attempts to join the English league system were thwarted because of their lack of adequate facilities, so they made do with entertaining the likes of Crystal Palace, Bristol City and Middlesbrough in friendlies on their Sophia Gardens home turf.

It’s also worth noting that Cardiff City’s roots as a football club lie in that most English of sports, cricket. The game of willow and leather is, of course, very popular in Wales and by 1899 no less than four Welsh counties – Glamorgan, Carmarthenshire, Monmouthshire and Denbighshire – had entered the Minor Counties championship. I can’t help but speculate on cricket’s appeal to Welsh sportsmen and suppose that, if getting anywhere takes you so long, you might as well stay there and play a long game to make it worth your while.

Nevertheless, cricket can realistically only be played in Wales during the summer months, so in order to keep their players fit and maintain team spirit for the rest of the year, it was not unusual for cricket clubs to play football as well. Wrexham, the oldest Welsh club, had done this in 1864, leading in turn to the establishment of the Football Association of Wales (FAW) 12 years later. In 1899, a Bristolian member of the Riverside Cricket Club in Cardiff by the name of Bartley Wilson pointed to the popularity of football in his native town and suggested the Welsh cricketers adopt the game.

In 1902 they merged with another football club, Riverside Albion (who were presumably English ex-pats), and when Cardiff was elevated to city status in 1905, they applied to the FAW to become ‘Cardiff City’, permission eventually granted in 1908 when the team entered the South Wales League. Cardiff was a booming hub of commerce, industry and culture and its football club soon began to echo that prosperity. The move from the cricket field at Sophia Gardens to Ninian Park in 1910 also marked their shift to professionalism and they entered the respectable Southern League Second Division, effectively English football’s fourth tier, that year.FN2

They were promoted in 1913, which meant that when the Football League absorbed much of the Southern League’s First Division to create the Third Division South [3] in 1920, Cardiff were firmly established in the English football hierarchy. They finished fourth in the 1919/20 post-war season, enough to place them straight into Division Two [2] during the merger, and in that first season in the Football League they were promoted to the top flight as runners-up.

Six years later and they really upset the apple cart when they took the FA Cup out of England for the first (and only) time, beating Arsenal at Wembley. Ironically, Cardiff’s success was credited to the performance of English left-half Billy Hardy in marking Charlie Buchan out of the game, while Arsenal’s Welsh goalkeeper Dan Lewis spilled a tame shot from Hughie Ferguson into the net for the only goal of an otherwise tight match.[2]

This was under the management of Fred Stewart during a 22-year spell. Unfortunately, by the time he retired in 1933, Cardiff had plummeted down the ladder to finish bottom of the Third Division South [3], having to re-apply for their Football League status. City’s fortunes seemed to be tied with Cardiff’s industrial strength, this having been hit badly as demand for Welsh coal declined – by the time Cardiff was declared the official Welsh capital in 1955, the Bluebirds were back in the First Division [1] after a post-war surge.

After spending most of the 1960s and ’70s in the Second Division [2], the ’80s and ’90s saw them yo-yoing between the third and fourth tiers. In 2000, former Wimbledon impresario Sam Hammam took over the club and threatened to change the team strip to a patriotic green, red and white. The club had been playing in blue since 1908,[3] around which time they also acquired the ‘Bluebirds’ nickname that would influence their club crests from the 1950s onwards.[4]

A decade later, of course, another takeover – by a pair of Malaysian businessmen – did result in the club’s strip changing, with two-and-a-half seasons played in red. Sense was finally seen in January 2015 when the infamous Vincent Tan bowed to supporter pressure[5] after the ‘re-brand’ overshadowed Cardiff’s first ever season in the Premier League [1]. Tan’s money was essential to the club as the previous regime and a move to the unimaginatively named Cardiff City Stadium in 2009 had left them with worrying debts, but his pound of flesh seemed to be a bizarre attempt to turn Cardiff into Malaysia’s favourite football club. Welsh teams may have had to look east to England to find a worthy level of football, but Southeast Asia was taking that concept too far.

Footnotes

References

- [1]Thomas, H., National Library of Wales, ‘Reshaping Welsh Railways – Beeching Report 50 years on’, March 3, 2013, http://www.llgc.org.uk/blog/?p=5670

- [2]Barrett, N., The Telegraph Complete History of British Football, 2013, Carlton Books, p. 45

- [3]Historical Football Kits, ‘Cardiff City’, http://www.historicalkits.co.uk/Cardiff_City/Cardiff_City.htm

- [4]The Beautiful History, ‘Cardiff City’, https://thebeautifulhistory.wordpress.com/clubs/cardiff-city/

- [5]The Guardian, ‘Cardiff revert to blue kit after Vincent Tan approves change’, January 9, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/football/2015/jan/09/cardiff-red-to-blue-kit-vincent-tan